The Motley Fool lists "10 Steps to Ruling Your Retirement". They are:

1. Get your assets in gear

2. Practice smart "asset location"

3. Run your numbers (figure out how much you need to retire)

4. Make your portfolio last

5. Crack your nest egg (how and when to make withdrawals)

6. Make the most of Social Security

7. Prepare your estate

8. Extend the life of your IRA

9. Cash in your house

10. Decide what you want to do in the future.

Most of these points assume you have assets to begin with and that you have built up value in homes and social security. The Retirement Confidence Survey challenges some of these assumptions with its finding that only 19% of people over age 55 have accumulated more than $250,000 in retirement savings (total savings and investments, not including the value of the primary residence). And only 23% of this same age group have $100,000-$249,999. Even if an investor has just enough to get into this top category, they will find it difficult to withdraw more than $1,000 per month and not risk reducing the principal (a nearly 5% annual withdrawal rate). Additionally, we have seen many view their homes as their retirement. But people have to live somewhere - for a home to be a retirement source would require selling and moving to a cheaper location. Others short circuit Social Security by drawing on it sooner than is prudent, resulting in lower lifetime benefits. There will be increasing opportunities for retirees to work part-time in the early retirement years and thereby delay drawing on Social Security.

Point 2 regarding asset location: Most investment professionals will recommend covering the universe with assets: some large cap growth, some large cap value, small cap, international, some bonds, etc. Several problems with this: first, environments of market stress have tended to impact all markets together. In statistical terms, this means all investments merge toward a correlation coefficient of one in difficult times - US Government notes have been one of the few investments that have been a recipient of investment flows during these difficult periods. This means that to disaster-proof a portfolio would require a slug of 5-10 year treasuries, that unfortunately provide little extra return during the good times. The biggest problem actually isn't that investments converge in difficult times, it is that investors blow out of long-term financial plans. We've all read about how stocks do so well over a 20 or 30 year period, but how many investors couldn't stand the pain in 2001-2002 and blew out of stocks, only to miss the ensuing rebound? There isn't much value in a long-term financial plan if there is a pattern of selling at the bottom and gradually returning to the market at much higher prices. We mentioned in an earlier post that if an investor had a goal of 15% per year for three years, that a year-one drop of 15% would require a return of nearly 34% in

each of the following two years to realize the average compounded return of 15%. The long-term average returns are dependent on being invested in the big up years. But many typical investors not only sell at the bottom but fail to capture the upside.

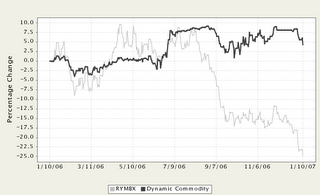

Our solution: investors should focus on where the values are at any time in the market. Even at the top of the market in 2000 there were many insurance stocks, home building companies, defense contractors and other stocks selling at single digit P/E ratios which subsequently rose 3-10 times in value over the next few years! We recommend that investors regularly review different segments of the market for value opportunities: Equities (large-cap, small-cap, value, growth, international, domestic, emerging markets, sectors,

REITs, etc.), Bonds (long-term, short-term,

TIPs, international, emerging markets, high-yield, municipal), Commodities (oil, industrial metals, agricultural, gold, commodity indexes) and currencies (strong or weak dollar). In addition to a wide variety of mutual funds, there are exchange-traded funds and closed-end funds covering all these sectors. An investor no longer needs to worry about individual securities with the proliferation of these vehicles. In fact, we would argue that for most part-time investors, owning and picking individual securities is a distraction that decreases returns. If your portfolio is always positioned in the value areas of the market, your need to worry decreases dramatically. Of course, cultivating a bit of a

contrarian way of looking at markets is required. Instead of asking, "whats going up?", ask "where are the values and can I identify a catalyst that might resolve the values in my favor?"

We're skipping around, but

MF's step 4 is to make your portfolio last. Two big points here: withdrawal rates and longevity insurance. Don't get caught up in the debate about whether you can withdraw 3%, 4%, 5% or 6% without risking your retirement. We find it best to determine your beginning level of

investable assets, and add an inflation factor to determine your baseline portfolio. You can withdraw some percentage of the current value of the portfolio up to the amount that exceeds the baseline. If you started the year with $1,000,000 and inflation was 2%, the ending baseline is $1,020,000. If your actual portfolio grew to $1,150,000 you can withdraw some percentage of $130,000. We would suggest that you withdraw somewhere between 4% of the baseline or the current account value (whichever is less) and 50% of the amount the portfolio is above the baseline; in this case, withdraw somewhere between $40,800 and $65,000. Where does the remainder go? It provides a cushion in the event the following year is a negative return year: the 4% minimum withdrawal will mostly be from year one's gains. Plus you have compounding working for you in year two which may push the current value even higher above the baseline. Why do we like this plan? it provides "bonuses" in retirement in the good years. What do we do when we're working 9 to 5? We put off swapping out the cars and remodeling the kitchen until we receive some windfalls in the form of bonuses or overtime. Why not do the same in retirement?

Second point: longevity insurance. People joke about spending their assets down to zero, then dying. Why not do it since there is a great way to accomplish this without risking getting to zero before getting to the end of your life? If investors purchase longevity insurance - insurance that pays out in the event the insured lives past a certain age - cash flow is assured. Purchasing a $10,000 policy at age 60 can provide as much as $700-$1,000 per month for life, once age 80 is reached. Putting $50,000 to $100,000 in such a policy can provide considerable piece of mind that the cash flow will be available later. The second great benefit is that one can spend much more up to age 80. If you know you are going to have several insurance policies kick in at age 80 it makes it much easier to spend down to zero through age 79 (although we wouldn't advise it). We suggest using several insurance companies to spread the company risk. Retirement can be fun (with such things as paying yourself bonuses) and worry free (longevity insurance). Why stress?

The WRA Strategies & Observations blog is written by officers of Wind River Advisors LLC, an SEC Registered Investment Advisor. See our web site for more information on strategies and account management:

Wind River Advisors.